Comeacqua

creation: Glen Blackhall, Riccardo Fazi, Fabio Ghidoni, Simona Frattini, Claudia Sorace, Massimo Troncanetti

stage dresses: Fiamma Benvignati

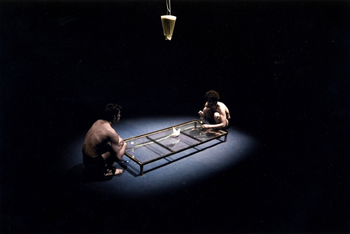

performance Glen Blackhall, Simon Blackhall

production Muta Imago 2006-07

stage dresses: Fiamma Benvignati

performance Glen Blackhall, Simon Blackhall

production Muta Imago 2006-07

We take water, and then a rope, some cellophane bags and a plexiglass table.

We make a home out of the table, we make it ship and tempest. We trap the water in the bags and we draw out of them objects that create worlds and visions. We freeze and chop the water, in order to understand how things work; we make it fall from above because when someone parts there can’t be good weather; we cut it out of the body, we light it up and shake it against glasses, because for someone it’s time to grow up; we colour it and we blow it into tubes because we’ve to understand each other; we dance on it, naked as babies, because life is not a circle, but a spiral.

If I should write today some drama notes on comeacqua, now that the show is fully done, definitive in its shape and contents, probably the first thing I’d do would be to pass through it again in my mind, eyes wide shut, in order to find out what it still tells me.

I would pause on the single scenes, I would think about the work in its whole, I would imagine its colours and movements, trying to tear away from it its central heart, that could have some sense for me, now.

I would discover a lot of hearts, because comeacqua doesn’t really have just one,

I would end up choosing one to talk about, to the prejudice of the others,

I would end up finding right words that can appear as new,

I would end up searching through the lines of texts that I lately met and that, in some ways, remembered me of the show, in its parts and in its whole.

I would end up doing something unsincere.

Rather, then, I go back to those april days of some time ago. I run through the early work again, through the foundation sources used then for the first time.

By chance I discover a passage written by Joseph Conrad that I had forgotten: it appears underlined with conviction, the lines marked more than once.

Usually, when we find again our autograph marks on the pages of books read in the past, we experiment a sort of strange embarassment, we perceive a distance between the “ourselves” of the past and the motivations that brought us to draw those pencil signs and the “ourselves” of today who finds them back, and smile, almost paternal.

But I take this passage, I transcribe it here and I read it again.

And I discover why I had chosen it amongst the others. And why I would do the same today.

“I need not tell you what it is to be knocking about in an open boat. I remember nights and days of calm when we pulled, we pulled, and the boat seemed to stand still, as if bewitched within the circle of the sea horizon. I remember the heat, the deluge of rain-squalls that kept us baling for dear life (but filled our water-cask), and I remember sixteen hours on end with a mouth dry as a cinder and a steering-oar over the

stern to keep my first command head on to a breaking sea. I did not know how good a man I was till then. I remember the drawn faces, the dejected figures of my two men, and I remember my youth and the feeling that will never come back any more–the feeling that I could last for ever, outlast the sea, the earth, and all men; the deceitful feeling that lures us on to joys, to perils, to love, to vain effort–to death; the triumphant conviction of strength, the heat of life in the handful of dust, the glow in the heart that with every year grows dim, grows cold, grows small, and expires–and expires, too soon–before life itself.”

It is still valid. The sense is the same.

Riccardo Fazi

It is still valid. The sense is the same.

Riccardo Fazi